|

| Gjon Mili, 1948 |

Category: Fashion

Casino wear

|

| George Condo x Adam Kimmel Fall/Winter 2010 |

National magazine, Volume 35

By Arthur Wellington Brayley, Arthur Wilson Tarbell, Joe Mitchell Chapple

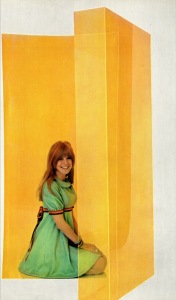

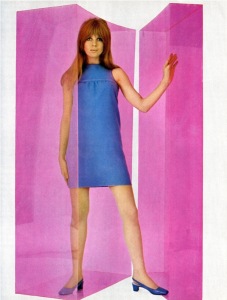

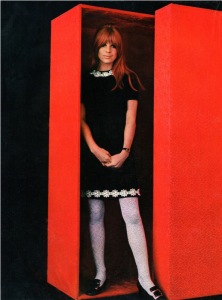

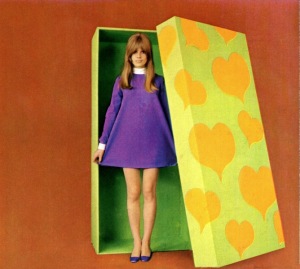

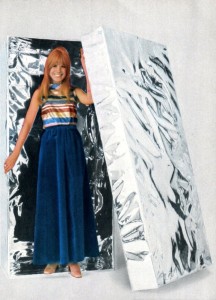

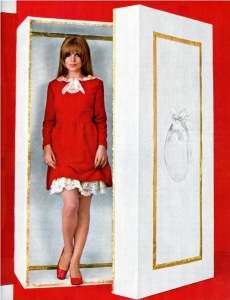

Faithfull

Source: Mademoiselle Age Tendre, N°27 Du 01-01-1967

via (Diet) Coke and Sympathy

Palm Springs. 1960

Edith Schiele in a Striped Dress

LB

Great design

La Cigale

|

| Christian Dior ~ Day Dress “La Cigale” Automne- Hiver 1952 [photo by Takashi Hatakeyama] |

This dress from the collections “Profile Line,” which have a distinctive sharp silhouette. In contrast to the slender upper body, the skirt spreads out three-dimensionally. Supported by a stiff petticoat, which has same form of the outer skirt, the skirt maintains a perfect silhouette.

Christian Dior led the golden age of Haute Couture in Paris since introducing the “New Look” in 1947. He created new silhouettes, such as the “Tulip line” and “A-line,” one after another for every season. Using a stiff interlining and bones, Dior created three-dimensional silhouettes.

The Kyoto Costume Institute

Harper’s Bazaar (September 1952) described “La Cigale” as built in “gray moiré, so heavy it looks like a pliant metal,” while Vogue (September 1, 1952) called it “a masterpiece of construction and execution.” In 1952, what has been called the Dior slouch was placed inside a severe International Style edifice. The devices customarily used to soften surface and silhouette in Dior are eschewed, and the dress becomes the housing of the fashionable posture now required by its apparent weight: the skirt is cantilevered at the hipbone—hip forward, stomach in, shoulders down, and the back long and rounded. Dior employed shaped pattern pieces to mold the bodice to the body and likewise to allow for the dilation at the hips.

American periodicals continued to promote Parisian couture lines after World War II, but they also included American design images and the ready-to-wear lines of Paris in order to make their publications relevant to a wide economic range of American women. “La Cigale” has the underpinnings of couture, but with its standard moiré, long, fitted sleeve, and smooth bodice and skirt cut, a facade of this cocktail piece could easily be adapted for the department store. American designers like Anne Fogarty and Ceil Chapman emulated the “New Look” line for cocktail wear, but used less luxurious fabrics and trims. Dior, along with French contemporary Jacques Fath and milliners Lilly Daché and John Fredericks, quickly saw the advantages of promoting cocktail clothing in the American ready-to-wear market, designing specifically for their more inexpensive lines: Dior New York, Jacques Fath for Joseph Halpert, Dachettes, and John Fredericks Charmers.

Fan dress

|

| Norman Parkinson, 1938 |

Norman Parkinson Portraits in Fashion by Robin Muir

A review by Benjamin Schwarz

After four lackluster years at Westminster, Norman Parkinson started his career in 1931 as an apprentice in the studios of a staid court photographer. By the end of the decade he had revolutionized the look of fashion pictures. Models had previously appeared cold, static, and studied; Parkinson aimed to “unbolt their knees,” and to suggest action and playfulness by taking “moving pictures with a still camera” — nothing like his snap of Pamela Minchin in sunglasses and a 1939 Fortnum and Mason swimsuit, leaping arms outstretched in front of the breakwaters on the Isle of Wight, had ever been seen in the fashion magazines. He got them out of the studioand onto the street, where he seemed to have caught them on the way to work (or at least a lunch date); into the muck of farm fields; and even onto the backs of ostriches and among herds of slumbering wild elephants (Parkinson pioneered the use of outdoor color photography and exotic locales in fashion shots). His style of “action realism” gave fashion photography not merely a sense of movement but an almost innocent exuberance (his 1955 picture New York, New York, of a joyful, sprinting Manhattan couple, epitomized the hopefulness of postwar young marrieds). But what made Parkinson a great photographer was his adoration — and, more important, admiration — of women (thanks probably to his closeness as a boy to his geriatric great-aunts and his indulgent mother), whom he knew to be the superior sex: “They are more courageous, more industrious, more honest, more direct,” he said — unpredictable adjectives coming from a man whose profession concentrated on women’s appearance. More than any other photographer, he captured the charm, intelligence, and humor of great feminine beauty, qualities abundantly on display here in his shots — taken from the mid-1940s to the mid-1950s — of the model and stage actress Wenda Rogerson, whom he married in 1947. (Rogerson was his third wife; they remained married until her death, forty years later.) As a model, Rogerson, in her Simpson’s suits and cashmere sweater sets, wearing sensible shoes or posed with an open umbrella by her side in the fog near Hyde Park Corner (an iconic image of the lingering sophistication of postwar London), had the astonishing ability to look at once cool and warm, elegant and jaunty; above all, she brought what she called a “witty underplay” to his pictures. Theirs is simply the most successful collaboration of photographer and model in the history of fashion, beside which the partnerships of David Bailey and Jean Shrimpton, and even Irving Penn and Lisa Fonssagrives, pale. Parkinson died in 1990, and his most professionally successful decades were his last three; but the book is divided into chapters by decade, and I found my interest flagging in the 1960s and diminished entirely in the 1970s and 1980s, as his photos, in keeping with the times, grew increasingly garish and outrageous — and as he, with his upturned moustache, in the too many photos with his models reproduced here, increasingly resembled a raffish, even louche, Indian Army colonel. (In fairness, Parkinson seems to have lost much of his enthusiasm for fashion photography after moving to Tobago, in 1963; he grew far more interested in portraiture, and became the Queen Mother’s favorite photographer.) But nothing can diminish his earlier work. Parkinson always insisted that he was a craftsman, not an artist, and he’d have dismissed the critic John Russell Taylor’s assessment that he was Sargent’s “logical successor.” We shouldn’t.

The Atlantic Monthly

September, 2004

|

| Amazon.com |