Category: LIFE

Mr. Hitchcock and Mr. Jenkins

|

| Peter Stackpole, Los Angeles, 1939

Alfred Hitchcock at home with his Sealyham terrier, Mr. Jenkins. (Picasso on the wall or reproduction?) The photographer described the portrait as “An Englishman spending a winter evening at home,” but Hitchcock titled it “A Dislike of American Fireplaces.” ➔ LIFE

|

The Tucker Cross

“September 1955, and the weather was getting worse. Then on the seventh day, a Sunday, I found the greatest single object of all. Eager to work faster, I took a water hose down to the bottom and turned on the jet to blast sand from the area below the brain coral. After carving a deep hole I turned the jet off. When the debris settled, my eyes fell on a gold cross, lying face down in the sand. I picked it up and turned it over.

Awe struck, I counted the large green emeralds on its face. There were seven of them, each as big as a musket ball. From small rings on the arms of the cross hung tiny gold nails, representing the nails in Christ’s hands, and at the foot was the ring for a third, which had been lost. The ornate carving, while beautiful, was somewhat crude, indicating that Indians had made the cross. It remains my most treasured discovery.”

|

|

Peter Stackpole, 1956

|

It was in November 1596, en route from Cartagena, Columbia to Cadiz, Spain, and laden with treasure, that the 350-ton merchant ship was wrecked on Bermuda’s inner reef.

She was discovered in 1950 by veteran shipwreck diver, Teddy Tucker and Robert Canten. Tucker knew that she was old and named her ‘The Old Spaniard’. However, it was only when he started to work on the site that he realised the true significance of his find.

Among the treasures recovered was a gold pectoral cross with seven emeralds, said to be one of the most valuable pieces of jewellery retrieved from any Spanish shipwreck. The cross was on display at the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo for many years. However, in 1975 when it was removed from its case during a royal visit, it was discovered that the cross had been stolen and replaced with a paste replica. Its whereabouts remain unknown. ➔ Bermuda Monetary Authority

Miss Gabor

|

| “Being jealous of a beautiful woman is not going to make you more beautiful.” |

Long before Anna Nicole Smith or Kim Kardashian, the life and career of Zsa Zsa Gabor personified that of a celebrity whose ascent to fame was due more to grabbing headlines than for any particular talent. Sister to “Green Acres” television star Eva Gabor, the future diva did pursue her own acting career and racked up a fairly impressive list of film and television credits, but she shone brightest on talk shows or within tabloid gossip pages where she delivered juicy stories about her many marriages and romantic encounters in her heavily accented and much imitated purr. She was still making news in her seventh and eighth decades – most notably for spending three days in jail after slapping a Beverly Hills traffic cop in 1989 – when she suddenly disappeared off the radar. Except for the occasional tabloid photo of a wheelchair-bound Gabor, her husband, “Prince” Frederic Prinz von Anhalt, spoke publicly on her behalf, while he made tabloid headlines of his own. Despite living a rather unorthodox life and sustaining a level of fame many felt was unjustified, Gabor sparkled brightly for over 60 years as a symbol of continental glamour and mystery. Keep reading ➔ Turner Classic Movies

|

| 3 Ring Circus |

New brilliantly colored stockings & shoes

Oh, where, Oh, where have all the great photographic films gone?…

Fernandel

FRANCINE

De tous les potins du quartier

Des ragots de la voisine

Des cancans du laitier

Par dessus tout ma belle

Ne va pas t’alarmer

De chaque fausse nouvelle

Des gens bien informés…

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Écouter les racontars

Des badauds par trop bavards

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Te laisser embobiner par les bobards

Ne crois pas qu’Hitler soit mal avec Staline

Et que les boches aient bombardé Madagascar

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Te laisser dégonfler par les âneries des canards

Méfie toi je te l demande

La TSF a des dangers de la sale propagande

Des speakers étrangers

Si parfois tu dégotes

Stuttgart à la Radio

Dis toi que tu serais idiote

D’en croire un traître mot

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Écouter les racontars

Du salopard de Stuttgart

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Te laisser embobiner par ces bobards

Quand je pense qu’il veut faire croire

Quand il jaspine

Que c’est un bon français

De Barbès-Rochechouard

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Te laisser dégonfler par ces discours là!

Le Führer d’une voix tendre

Nous redit chaque samedi

Je ne veux plus rien prendre

Maintenant que j’ai tout repris

J’adore l’Angleterre

J’adore les Français

Pourquoi me faire la guerre

Quand je veux qu’on me fiche la paix!

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Écouter les racontars

Du plus barbant des barbares

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Te laisser embobiner par ses bobards

S’il prend pour nous désarmer sa voix câline

C’est pour mieux nous tomber dessus un peu plus tard

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Te laisser dégonfler par ces propos de paix

Faut pas, faut pas Francine

Te laisser dégonfler par ces propos de paix, Si! Na!

paroles: A. Willemetz, musique: C. Oberfeld, 1939

The great cinematographer Jack Cardiff

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger – with Cardiff, the composer Brian Easdale and the designer Alfred Junge – took British films into an area of fantasy and romance previously dominated by European expressionism and spangled American spectaculars.

|

| Black Narcissus |

In The Red Shoes – the story of a ballerina’s fatal obsession with her art – Cardiff’s fluid camera and bold use of colour created a unity from naturalistic, staged and dream sequences. He had a remarkable gift for telling a story with colours, and used red to striking effect: there is the red dress and lipstick of Kathleen Byron’s lovesick nun in Black Narcissus, and the red ballet shoes that torment Moira Shearer’s ballerina.

|

| The Red Shoes |

Cardiff could find eroticism latent in the most unpromising circumstances, and few were able to light women as he could: his close-ups of burning eyes and moist lips revealed passionate depths in such demure actresses as Deborah Kerr and Kim Hunter.

|

| The Prince and the Showgirl |

He also survived working with John Huston, for whom he filmed The African Queen (1951), a project of celebrated hardship made in colour, with Huston at his most perverse, more interested in hunting than in filming.

|

| The African Queen |

For King Vidor, Cardiff filmed the gargantuan battle scenes in the American/Italian production of War and Peace (1956), for which he received one of his numerous Oscar nominations. In the event, he won only once, for Black Narcissus.

|

| War and Peace |

The son of music hall performers, Jack Cardiff was born at Great Yarmouth on September 18 1914. His parents toured extensively, and Jack later claimed to have attended a multitude of schools. He made his film debut at the age of four, and in a subsequent role he played a boy who dies after being run over – his demise took three days to film, a harrowing experience for his parents since his elder brother had died in infancy.

|

| Girl on a Motorcycle |

Also known as Naked Under Leather, it stars Marianne Faithfull as a continental bimbo who leaves her sleeping husband, zips herself into black leather, straddles an enormous motorbike and thrashes off to seek the heartless intellectual (Alain Delon), who alone can satisfy. At a sexual climax induced by her beloved machine, she crashes spectacularly and dies. One feature of this fetishistic curio is that even on the most extreme bends the motorcycle never appears to deviate from the vertical.

|

| Alain Delon and Marianne Faithfull |

Another peculiar venture was The Scent of Mystery (1960). Made for that quintessential showman Michael Todd, it was the first film to be presented in Odorama, or “Smell-O-Vision”, a system that released odours in a cinema so that the audience could “smell” what was happening on the screen.

In 1994 the Los Angeles Society of Cinematographers presented Cardiff with its international award for outstanding achievement; the next year he received a lifetime achievement award from the British Society of Cinematographers. In 2000 he was appointed OBE, and the following year he was awarded an honorary Oscar.

Rocks!

|

| Cartier, Tiffany |

|

|

| The famous Hope Diamond |

|

|

| Taylor-Burton Diamond |

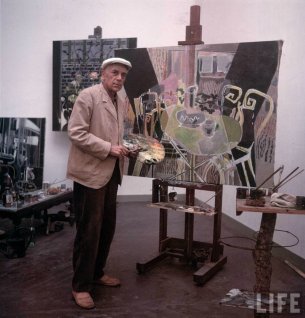

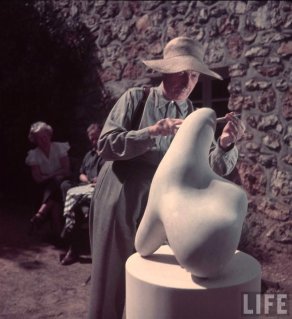

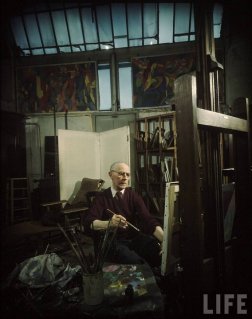

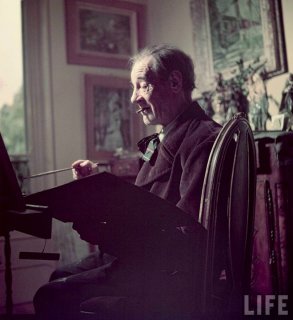

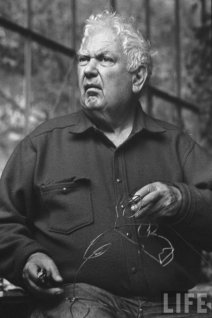

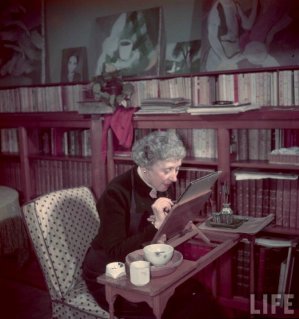

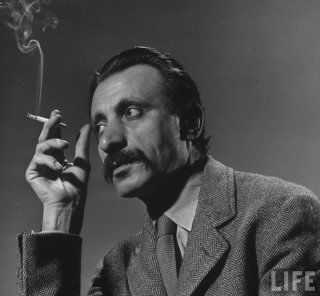

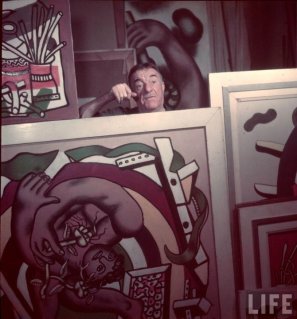

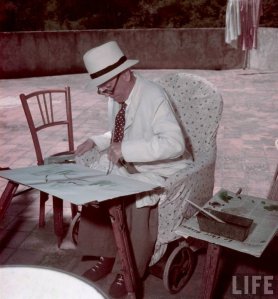

Great LIFE photographer Gjon Mili’s portraits of the Artists

The series of photographs Picasso’s light drawings were made with a small flashlight in a dark room. The images vanished almost as soon as they were created.

|

| Pablo Picasso |

|

|

| Pablo Picasso |

|

| Giorgio de Chirico |

|

| Georges Braque |

|

| Jean Arp |

|

| Jacques Lipschitz |

|

| Jacques Villon |

|

| Henri Matisse |

|

| Henri Matisse |

|

| Maurice Utrillo |

|

| Giacomo Balla |

|

| Alexander Calder |

|

| Marie Laurencin |

|

| Arshile Gorky |

|

| Fernand Léger |

|

| Marc Chagall |

|

| Maurice Vlaminck |

|

| Raoul Dufy |

|

| Salvador Dali |

|

||

| Georges Rouault |